Tale of Two Bills: Competing Visions of NSF’s Future Make Their Way Through Congress

Over the last two months, competing visions of the future of the National Science Foundation have been making their way through the House and Senate. And much like the famous opening line of Tale of Two Cities, their paths could not be more dissimilar. On the House side, the National Science Foundation for the Future Act has made deliberative and bipartisan progress through the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee. Meanwhile, on the Senate side, the Endless Frontier Act has been introduced; pulled, reworked, and reintroduced; heavily amended during a marathon Senate Commerce Committee hearing; and is now before the full Senate undergoing another round of amendments. Very different paths.

Let’s start with the Senate and the Endless Frontier Act. This has been a moving target with major changes to the bill happening at every legislative step. Regular readers will recall that the bill was first introduced in mid-April; it was almost immediately pulled from a scheduled Senate Commerce Committee hearing because of a large number of amendments, which is a sign that the legislation would not progress as written. The legislation was reworked, incorporating as many amendments as possible, and was reintroduced at a marathon 6+ hour hearing of the Senate Commerce Committee. At that hearing, the bill was further changed.

The new Endless Frontier Act is quite different. The bill still establishes a new Directorate for Technology & Innovation (abbreviated TD for “Tech Directorate”) with the directorate’s program managers expected to operate like their counterparts at DARPA. As well, the ten Technology Focus Areas (which are largely unchanged from previous versions) are now required to be reviewed every year; it had been every three years. Additionally, the new language transfers several current efforts of NSF into the new directorate. Most make sense and aren’t problematic, such as the Convergence Accelerator and the I-Corps programs; however, it does transfer the National AI Research Institutes program out of CISE with potential ramifications for the CS research community.

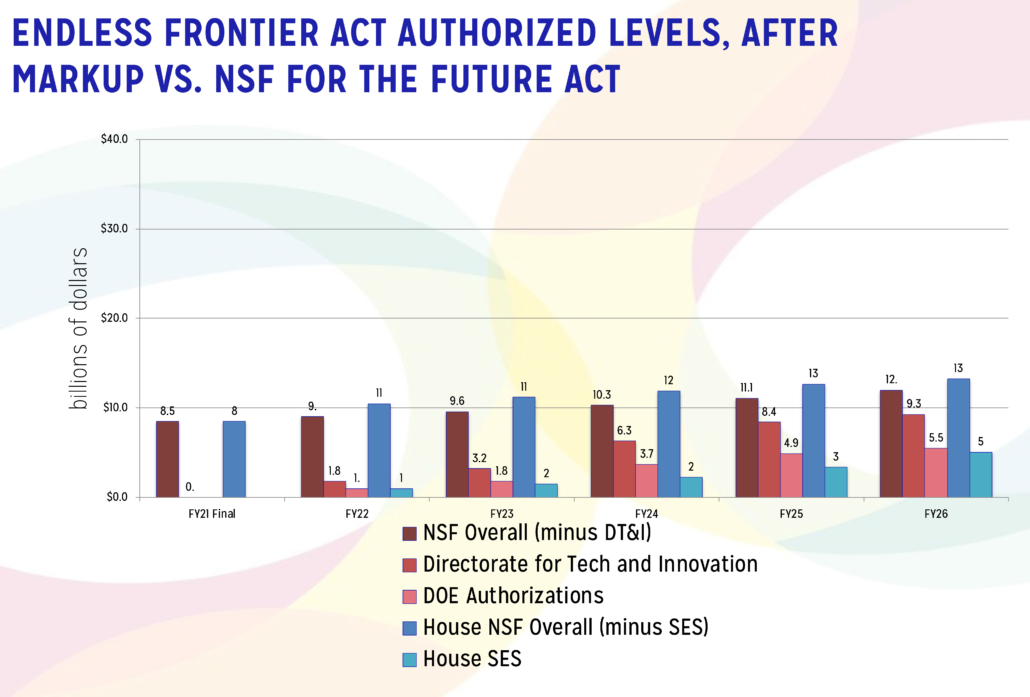

The funding authorizations are also different from previous versions. NSF, minus the new TD, gets a plus up of 30 percent over five years — a rough average of 5.5 percent a year. The Foundation would grow from just under $9 billion in Fiscal Year 2022 to just over $11 billion in 2026. In a significant change from previous versions of the bill, the new tech directorate would receive just over $40 billion in authorizations over five years, starting out at $2.5B in FY22 and growing to $14.9B in FY26, well down from the $100 billion originally proposed. As in the previous versions, that funding would be targeted to R&D activities in the key focus areas, support for scholarships and fellowships, test beds, efforts to improve academic tech transfer, and capacity building at historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) and other minority serving institutions (MSIs). Additionally, in perhaps the most contentious change, the Department of Energy would also receive a $16 billion funding authorization over five years to perform research in the Technology Focus Areas. Guidance to DOE on how to spend the authorization is limited to “R&D and address[ing] the energy-related supply chain activities within the key focus areas.” Much of these DOE funds come directly at the expense of the new directorate; in fact, Senator Young (R-IN), one of the co-sponsors of EFA, called this amendment a “poison pill” during the committee hearing.

There are other provisions of note in the new language. Perhaps the most significant is a new emphasis on the geographic diversity of which states receive NSF funds. Senator Wicker (R-MS), the Ranking Member of the Senate Commerce Committee, championed this issue during previous hearings. The new language now requires NSF to use “at least 20 percent” of the funding provided to the TD to carry out the EPSCoR program, which helps states who historically receive less NSF funding to build up their research capacity. In addition, the legislation also requires that “at least 20 percent” of all NSF funding must be used to carry out EPSCoR. Senator Wicker called this a “quantum leap” in terms of providing geographic diversity; seeing as last year NSF used about 3 percent of its research funding for EPSCoR, the Senator’s description is close to the mark. Provisions echoing this are throughout the legislation language for almost everything that is authorized.

There are also new provisions concerning research security, putting potentially greater scrutiny on controls for the research funded at the new directorate. There are two sections that are potentially concerning for the research community (legislative text in full). One section (Sec. 2303) puts prohibitions and reporting requirements on principal investigators from taking part in foreign talent recruit programs, with complete bans on recruitment programs from China, Iran, Russia, and North Korea. The second section (Sec. 2304) is about “Additional Requirements for Directorate Research Security;” while vaguely worded, it could potentially lay the groundwork for putting controls on the research performed in the new directorate. The language is not clear as to what those controls would be, but it leans heavily on NSF to figure out how to protect the research in the technology focus areas.

While not a clean process, EFA did pass the Senate Commerce Committee with a bipartisan vote of 24-4. It was then moved quickly to the Senate floor last week, combined into a package with other legislation, and renamed the “United States Innovation and Competition Act of 2021.” The bill is now 1400+ pages and has several new sections corresponding to several pieces of other legislation considered by other Senate committees. A major addition to the package is the “Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors (CHIPS) for America Fund,” which provides $52 billion in emergency appropriations for semiconductor R&D. These funds are to both help bolster and expand the semiconductor industry in the United States and to foster research on next generation chips. Much of this legislative package deals with responding to the rise of China as a peer-rival to the US, so there are many sections handling foreign policy matters. But there are also sections dealing with research security, such as subjecting foreign donations to US academic institutions to oversight by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US (CFIUS). In short, this is no longer an authorization bill; it is much bigger.

The legislation was expected to be finalized and voted on before the Memorial Day weekend, but that has since changed; it is now expected to be handled in June when the Senate reconvenes after their holiday recess.

On the other side of Capitol Hill, the response has been very different. After the Senate Commerce Committee passed EFA, Rep. Frank Lucas (R-OK), the Ranking Member of the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee put out a statement saying much of the Senate bill lacks a clear vision for NSF and is weighed down by special interest provisions. Rep. Lucas’ view should be seen as a barometer of Republican support for NSF; they will advocate for increases but only to an extent, and those increases must be well justified.

To that end, the House Science, Space, and Technology Committee has been moving their own NSF bill. Regular readers will recall that Chairwoman Eddie Bernice Johnson (D-TX) and Ranking Member Lucas, along with Subcommittee on Research and Technology Chairwoman Haley Stevens (D-MI) and Ranking Member Michael Waltz (R-FL), introduced the National Science Foundation for the Future Act in late March and have been holding several hearings about NSF since. On May 13th the Subcommittee on Research and Technology held a markup of the legislation. In contrast with the Senate, the legislation is unchanged since introduction, it received only a few non-controversial amendments during this hearing, and it was passed unanimously on a voice vote. The next step is for the full Science Committee to markup the legislation; that’s likely to happen in early June. Consideration on the House floor should happen soon after. The Science Committee is also beginning the process of reauthorizing the Department of Energy’s Office of Science; we’ll have more details on that in a future post.

CRA endorsed the NSF for the Future Act in early May.

What happens next? At some point, these two different views on NSF’s future have to be reconciled and a compromise worked out. The main draw for EFA has been its higher funding level for the agency but, because of all the amendments, it is now much closer to the levels in the NSF for the Future Act; that is actually good from a compromise perspective. But since the USICA covers so many topics, many of which the House has not begun to cover, will the House even consider a conference? Or would it attempt to break the matter up into smaller pieces? Would the Senate agree to go along with that approach? It’s not unusual for legislation to remain idle before there’s an agreement between the two chambers, but that idleness can last months. Should the Senate pass the EFA/USICA bill, the likelihood that something gets worked out is high. But the timeframe is TBD. We’ll keep tracking all the developments, so please check back for more information.