The State of African-Americans in Computer Science – The Need to Increase Representation

In the field of computer science, African-Americans are considered one of many groups who are underrepresented. Even though African-Americans comprise 13.2% of the U.S. population [8], their current representation in computer science is not proportional. This underrepresentation is especially visible in the industry and academic employment sectors of computer science.

This reality has caused many to question why diversity is scarce among employees at major technology companies in the United States [3]. Within the academy, the issue of underrepresentation, along with concerns regarding the recruitment, retention, and production of African-American computer scientists, has been brought to the forefront.

In a direct effort to address African-American underrepresentation in computer science, the National Science Foundation (NSF) has funded a project known as the Institute for African-American Mentoring in Computing Sciences (or iAAMCS, pronounced “i am c s”). iAAMCS serves as a national resource for African-American students and faculty who aspire to pursue a career in computer science. Furthermore, iAAMCS provides unique opportunities to expose African-American students, who may lack knowledge of the field, to the idea of pursuing computer science as a career.

In this article, we examine the current underrepresentation of African-Americans in the industry sector of computer science and efforts to mitigate this problem. We also discuss similar occurrences within academic settings of computer science. Finally, we explain how iAAMCS can serve as a platform for increasing the representation of African-Americans in the field of computer science.

Industry

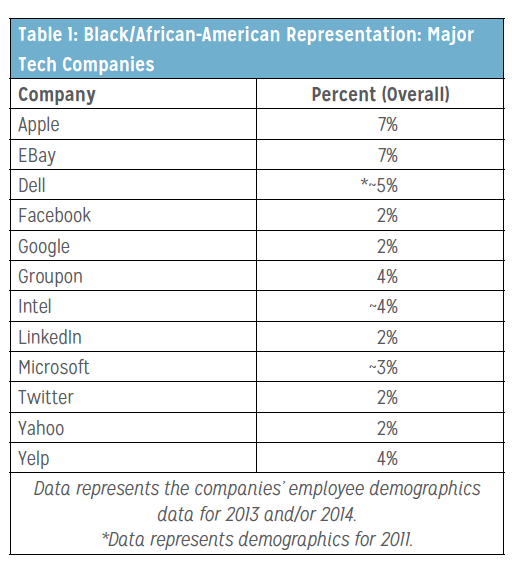

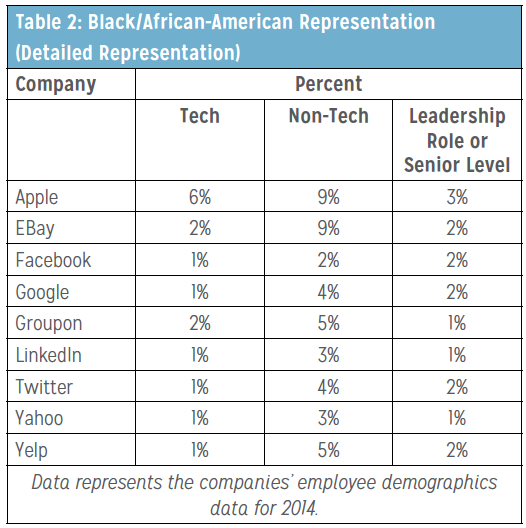

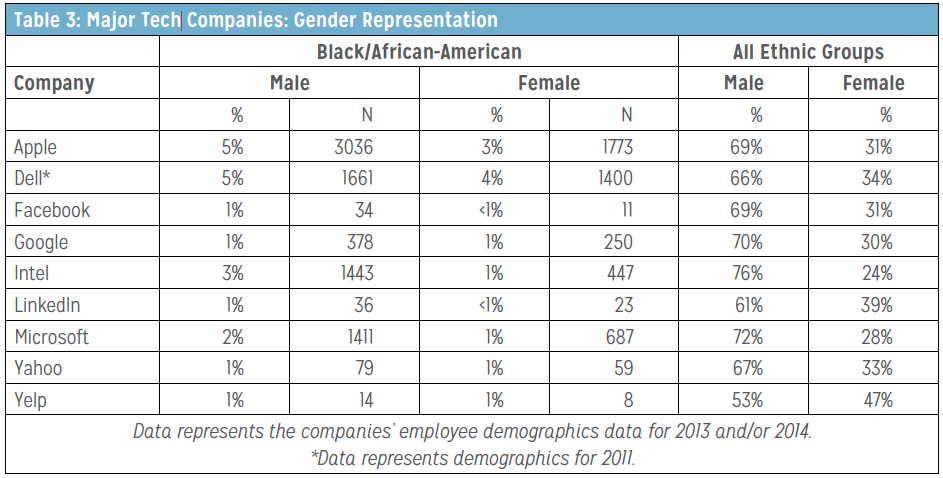

Major technology companies, particularly ones located in Silicon Valley, are currently facing the challenge of diversifying their employee base [4, 9]. Lacking adequate representation of African-Americans can be considered one of the many challenges that these companies face when it comes to employee diversity. For instance, Table 1 provides self-reported data from companies in Silicon Valley and other notable companies regarding the representation of Black/African-American employees. Furthermore, Table 2 lists percentages of Blacks/African-Americans in position-specific jobs at many of the Silicon Valley companies, while Table 3 displays related percentages based on gender. According to the data listed in the aforementioned tables, Blacks/African-Americans are significantly underrepresented in these companies. From a gender standpoint, Black/African-American females are found to exhibit a lower representation than their male counterparts, which also highlights a related issue of female underrepresentation within these companies. These data can be found on these companies’ websites, within their EEO-1 report, and/or via the Open Diversity Data project [6].

One company that has already taken an initiative to address minority underrepresentation among its employee base is Intel. Specifically, Intel has committed $300 million over the next five years to improve the diversity of its employees [9]. And Intel is already showing an increase in the hiring of African-Americans and other minority groups, according to its recent mid-year report [5].

One company that has already taken an initiative to address minority underrepresentation among its employee base is Intel. Specifically, Intel has committed $300 million over the next five years to improve the diversity of its employees [9]. And Intel is already showing an increase in the hiring of African-Americans and other minority groups, according to its recent mid-year report [5].

Postsecondary Education

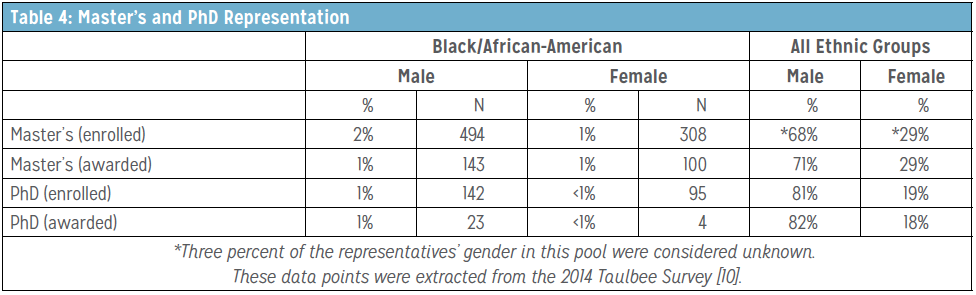

Similar to industry, African-Americans are found to be significantly underrepresented in postsecondary education. This trend is most prevalent amongst Master’s and PhD production, as well as faculty representation. According to the 2014 Taulbee Survey, African-Americans represent approximately 2.4% and 1.5% of Master’s and PhD recipients respectively in computer science and related fields [10]. Table 4 provides detailed percentages of both African-American male and female representation regarding Master’s and PhD enrollment and awardees. In addition, this table lists percentages of all male and female representation at these respective levels. From the statistics listed in Table 4, it can be concluded that: 1) both African-American males and females are significantly underrepresented at the Master’s and PhD levels of computer science and related fields, and 2) African-American females (and/or all females in this case) exhibit a much lower representation than their male counterparts.

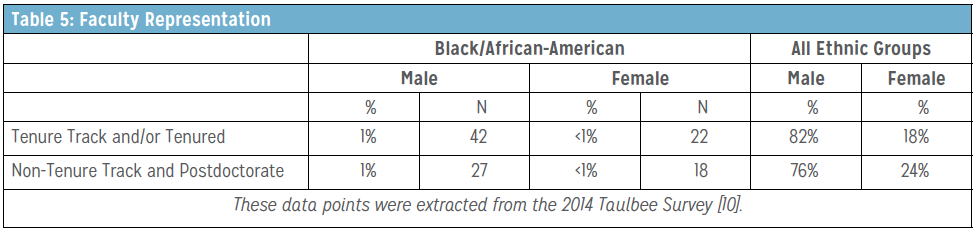

At the professorate level, African-Americans represent only 1.7% of tenured and non-tenured faculty in computer science and related departments [10]. Table 5 lists the percentages of African-American male and female professors who are either on the tenure track and/or currently tenured, percentages of faculty who currently serve in either non-tenure track positions or as postdoctorates, and a total percentage of faculty representation by gender. Similar to Table 4, the statistics in Table 5 reveal the same trend of African-American male and female underrepresentation. Moreover, African-American females (and/or all females in this case) display a much lower representation than their male counterparts.

At the professorate level, African-Americans represent only 1.7% of tenured and non-tenured faculty in computer science and related departments [10]. Table 5 lists the percentages of African-American male and female professors who are either on the tenure track and/or currently tenured, percentages of faculty who currently serve in either non-tenure track positions or as postdoctorates, and a total percentage of faculty representation by gender. Similar to Table 4, the statistics in Table 5 reveal the same trend of African-American male and female underrepresentation. Moreover, African-American females (and/or all females in this case) display a much lower representation than their male counterparts.

This underrepresentation of African-American faculty also imposes an additional barrier for African-American students to potentially obtain same-race mentorships, if desired. Prior research has shown that same-race (and same-gender) mentorship can provide more psychological support than cross-race (and cross-gender) relationships [7]. In addition, African-American students, who have a mentor of a difference race, often have contrasting, if not conflicting, perspectives about mentoring [4].

This underrepresentation of African-American faculty also imposes an additional barrier for African-American students to potentially obtain same-race mentorships, if desired. Prior research has shown that same-race (and same-gender) mentorship can provide more psychological support than cross-race (and cross-gender) relationships [7]. In addition, African-American students, who have a mentor of a difference race, often have contrasting, if not conflicting, perspectives about mentoring [4].

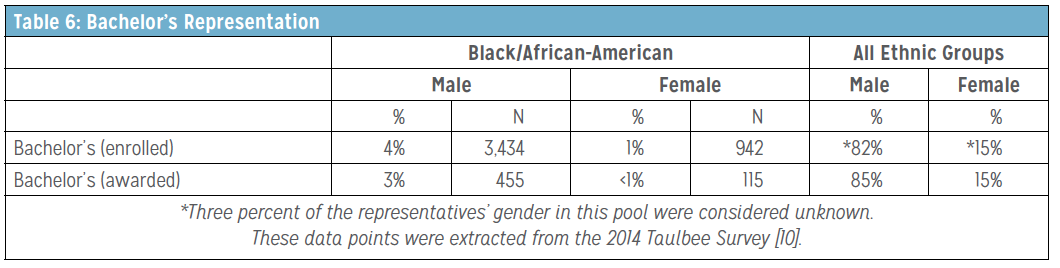

At the Bachelor’s level, providing African-American students with effective mentorship could be critical if they are to continue in computer science. Currently, there is a higher representation (5.6%) of African-Americans in computing fields at the Bachelor’s level [10]. This indicates two things: 1) a leak exists between the Bachelor’s degree and graduate school in the computer science pipeline, and 2) a sufficient pool of African-American prospects may already exist to either pursue graduate education in computing or secure positions in industry. Table 6 lists the percentages of African-American male and female representation regarding Bachelor’s enrollment and awardees. In addition, this table displays percentages of all male and female representation at this level. Even though African-American students do exhibit a higher representation at the Bachelor’s level, these statistics reveal that: 1) both male and female representation for this group is still significantly underrepresented, and 2) African-American females (and/or all females in this case) exhibit an even lower representation than their male counterparts.

iAAMCS

iAAMCS is an NSF Broadening Participation in Computing (BPC) Alliance member (see http://www.iaamcs.org). The mission of iAAMCS is to: 1) increase the number of African-Americans receiving PhDs in computing sciences; 2) promote and engage students in teaching and training opportunities; and 3) add more diverse researchers into the advanced technology workforce. Moreover, reversing the trend of African-American underrepresentation in computer science is one of the key objectives of iAAMCS.

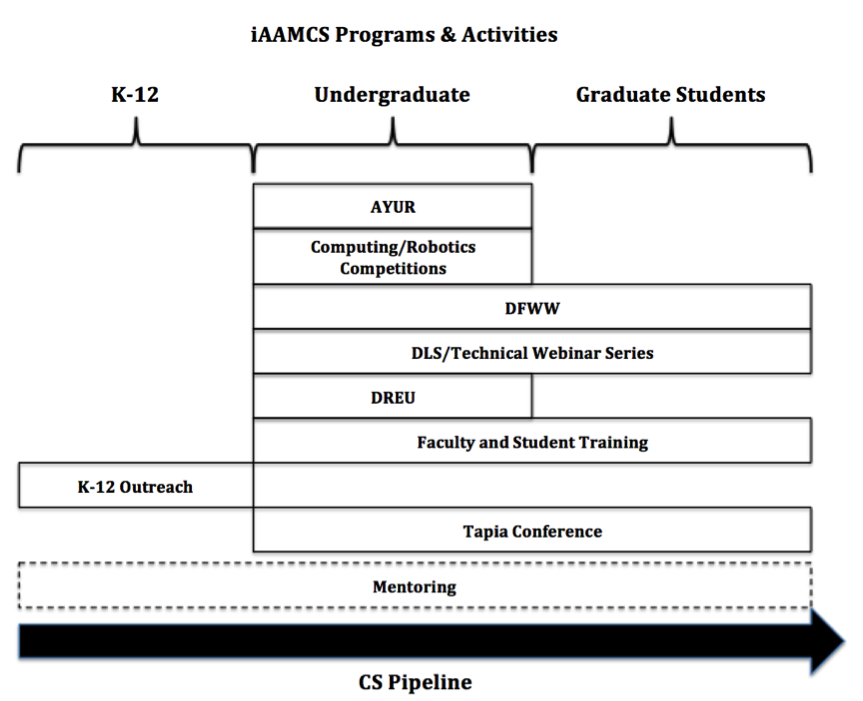

iAAMCS provides a variety of programs and activities to assist African-American students as they matriculate through the computer science pipeline.

Figure 1: iAAMCS Programs and Activities Continuum

These include:

- Faculty and student training

- Academic Year Undergraduate Research (AYUR)

- Distributed Research Experiences for Undergraduates (DREU)

- Technical webinars and Distinguished Lecture Series (DLS)

- Distinguished Fellows Writing Workshop (DFWW)

- K-12 outreach

- Computing and robotics competitions

- Tapia Celebration of Diversity in Computing Conference

These programs and activities serve African-American students at various stages throughout the computer science pipeline. Figure 1 provides a continuum that lists each program and activity currently offered by iAAMCS. This continuum also pinpoints the targeted audience that these programs and activities typically serve.

Many of these programs serve undergraduate and graduate students. The programs also attempt to influence an increase in the retention of African-American students at these respective stages of the computer science pipeline. However, the recruitment of African-American students is also important. As such, these programs provide a platform for recruiting more African-American students who aspire to pursue computer science as a career choice. In addition, a K-12 outreach component was recently added to iAAMCS with the intent to expose and recruit African-American students to computer science earlier in their educational trajectory.

As previously mentioned, providing mentorship to African-American students as they matriculate through the computer science pipeline is important. As iAAMCS begins its third year as an organization, enhancing how current and future iAAMCS participants are mentored will be a primary focus. As highlighted in the continuum (Figure 1), the mentorship aspect of iAAMCS will cover participants at every stage of the computer science pipeline. Through mentorship, iAAMCS aims to expose participants to role models who resemble them, while also monitoring their ability to develop the skill sets necessary to secure careers in industry or academia.

Conclusion

There is a need to increase the presence of African-Americans in computer science in both the postsecondary and industry sectors of computer science. Improving the diversity and inclusion of African-Americans, and other underrepresented groups, in the workforce is a key driver to enhancing creative thinking [1] and innovation [2]. From a gender standpoint, there also is a need to increase female representation of African-Americans (and of all underrepresented groups) in the field.

iAAMCS is an organization that possesses the capacity for improving the representation of African-Americans in computer science. With mentorship as the key underpinning of the iAAMCS, upward shifts in the numbers of African-Americans pursuing and receiving PhDs in computer science could soon be achieved. Likewise, increased representation at the faculty/professorate level of computer science, as well as a rise in the number of African-Americans being employed at major technology companies, could be a tangible and welcome outcome.

References

- Baumgartner, J. “Why Diversity is the Mother of Creativity.” InnovationManagement.se (2013); http://www.innovationmanagement.se/imtool-articles/why-diversity-is-the-mother-of-creativity/.

- “Global Diversity and Inclusion: Fostering Innovation Through a Diverse Workforce.” Forbes Insights (2015); http://forbes.com/forbesinsights.

- Guynn, J. “Intel pledges diversity by 2020, invests $300 million.” USA Today (2015); http://www.usatoday.com.

- Harley, D. A. (2005). “In a different voice: An African-American woman’s experiences in the rehabilitation and higher education realm.” Rehabilitation Education – Special Issue: The Role of Women in Rehabilitation Counselor Education, 15(1), and 37-45.

- “Intel Diversity in Technology.” Intel-Mid-Year Report 2015. accessed August 12, 2015, http://www.intel.com/content/www/us/en/diversity/diversity-in-technology-intel-2015-midyear-progress-report.html.

- Open Diversity Data Project, accessed July 30, 2015, http://opendiversitydata.org/.

- Smith, J. W., Smith, W. J., & Markham, S. E. (2000). “Diversity Issues In Mentoring Academic Faculty.” Journal of Career Development, 26(4), 251-262.

- S. Census Bureau, USA QuickFacts, accessed August 10, 2015, http://quickfacts.census.gov/qfd/states/00000.html.

- Vara, V. “Can Intel make silicon valley more diverse?” The New Yorker (2015); http://www.newyorker.com.

- Zweben, S., and Bizot, B. “2014 Taulbee Survey.” Computing Research News vol. 27, no. 5 (2015).

Author Information

Edward C. Dillon, Jr. (ecdillon@cise.ufl.edu) is the iAAMCS project manager and a postdoctoral associate in the Computer and Information Science and Engineering Department at the University of Florida.

Juan E. Gilbert (juan@ufl.edu) holds the Andrew Banks Family Preeminence Endowed Chair and is the Department Chair of the Computer and Information Science and Engineering Department at the University of Florida where he leads the Human-Experience Research Lab. He is also the Director of iAAMCS.

Jerlando F. L. Jackson (jjackson@education.wisc.edu) is the Vilas Distinguished Professor of Higher Education and the director and chief research scientist of Wisconsin’s Equity and Inclusion Laboratory (Wei LAB) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

LaVar J. Charleston (charleston@wisc.edu) is the assistant director and a senior research associate at Wisconsin’s Equity and Inclusion Laboratory (Wei LAB) within the Wisconsin Center for Education Research at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.