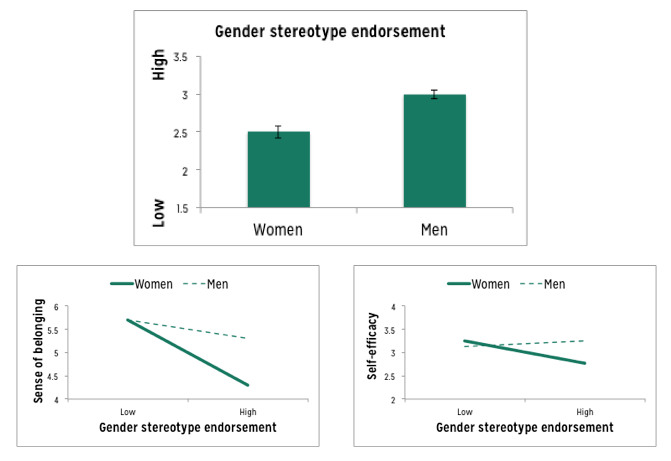

Gender Stereotype Endorsement

One hundred eighteen graduate students (n = 75 women, n= 143 men) indicated (a) the degree to which they endorse the stereotype that women are less capable in computing that men; (b) how much they felt they “belong” in computing and (c) their self-efficacy in computing. Men endorsed the negative stereotype to a greater degree than women, p < .01. However, among women, stronger endorsement of the negatively stereotype was associated with a lower sense of belonging and lower sense efficacy in computing, ps < .05; men’s stereotype endorsement was unrelated to their belonging and self-efficacy. These results highlight the importance of fostering a stereotype-free training environment so that women’s self-concept in computing is unconstrained by negative cultural beliefs about their ability.

Note: Stereotype endorsement Stereotype endorsement was assessed by asking students to indicate their agreement with and aggregating the following items: Although some women might be good at computing, women in general tend to be better at other things; there is no doubt in my mind that women are just as talented at computing as men are (reverse scored); Computing fits men’s personalities better than women’s; Computing seems to come more naturally to men than women, using a scale ranging from (1) Strongly disagree – (7) Strongly agree. Belonging was assessed by asking students to indicate their agreement with and aggregating the following items: I feel like I belong in computing; I feel like an outsider in the computing community (reverse scored); I feel welcomed in the computing community; Computing is a big part of who I am; I do not have much in common with other people in computing (reverse scored); I see myself as a computing person, using a scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree – (7) strongly agree. Self-efficacy was assessed by aggregating the following items regarding students’ confidence that they could do the following: Become the go-to person for expertise in your content area; Publish papers as first author in the top journals of your field; Discuss theory with senior members of your field; Win awards for your work; Articulate thoughtful answers to theoretical questions about your work during a presentation; Successfully receive funding for a grant on which you are the Principle Investigator (PI); Become a respected member of the research community in your research area, using a scale ranging from (1) Not at all confident – (5) Extremely confident.

This analysis brought to you by the CRA’s Center for Evaluating the Research Pipeline (CERP). Want CERP to do comparative evaluation for your program or intervention? Contact cerp@cra.org to learn more. Be sure to also visit our website at https://cra.org/cerp/.

This analysis brought to you by the CRA’s Center for Evaluating the Research Pipeline (CERP). Want CERP to do comparative evaluation for your program or intervention? Contact cerp@cra.org to learn more. Be sure to also visit our website at https://cra.org/cerp/.