Financial Aspects of Doctoral Study for Women in Computing, 1998-2013

Background

This article examines trends for women and men in three financial aspects of doctoral study: the primary source of doctoral funding, the source of postdoctoral funding for those choosing a postdoctorate, and starting salaries for new Ph.D.s.

These analyses are part of a larger project examining trends in the representation of women in computing from 1990-2013. As part of that project, we licensed data from the National Science Foundation’s Survey of Earned Doctorates (SED). The SED is sent each fall to every individual who received a research doctorate from an accredited U.S. institution in the previous academic year. It asks about the respondent’s educational background, demographics, and postgraduation plans. In 2013, 92 percent of doctoral recipients completed the survey. We included data on SED respondents whose field of doctoral program was in the disciplines of (SED codes are listed in the parenthesis): computer science (400), computer engineering (321), information science & systems (410), robotics (415), and computer & information systems, other (419).

We previously used SED data to analyze the baccalaureate origins of women doctoral graduates (Bizot and Zweben, 2015) and plan forthcoming articles on time to degree and postgraduation employment plans.

Funding for Doctoral Study

Some research has shown that students who support their doctoral work with a teaching assistantship (TA) believe it causes them to take more time to complete their degree (Schmidt, 2009). Further, it is known that women, on average, take longer than men to complete a doctorate in computing (Bizot, 2014). Therefore, we wanted to know if women were more likely than men to support their doctoral work with a TA.

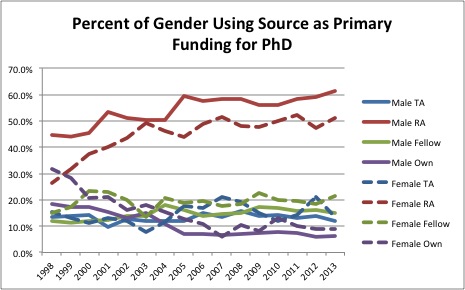

Figure 1 shows the percent of each gender whose primary source of doctoral funding was a research assistantship (RA), teaching assistantship (TA), graduate fellowship or dissertation fellowship (Fellow), or own resources (Own). Additional sources of funding in the SED data include foreign government, employer, and other; too few students were funded by any of these mechanisms to report trends.

Funding data trends are examined from 1998-2013 because of a change in the way the data was coded and reported in 1998.

The percent of both men and women who fund their doctoral studies primarily through a research assistantship increased steadily over the time period, but a higher percent of males than females fund their studies this way. Conversely, the percent of those funding their doctoral studies with their own resources has decreased steadily, but a higher percentage of females than males fund their studies this way in all years.

For men, there is a significant increasing trend in the percent funding their studies through a fellowship, but most of the change seems to be before 2004. The trend is not significant for women. There is no significant trend in TA funding for either men or women.

Figure 1. Percent of Gender Using Source as Primary Funding for Ph.D.

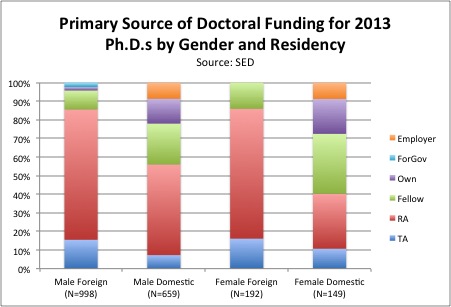

Overall, foreign and domestic students have somewhat different sources of funding. Figure 2 shows the main source of funding for students completing their degree in 2013, by gender and residency groups. Male and female foreign students have very similar patterns of TA and RA funding, but some males also had government or own resource funding while females did not. Employer funding and own resource funding are more likely and TA funding is less likely for domestic students, both male and female, than for foreign students. Thus, the fact that a higher percentage of women than men use their own funds for their doctoral study is totally due to domestic students. Finally, domestic women are as likely to have fellowship funding as RA funding, the only group for which this is true. In theory fellowship funding, with its absence of a work requirement, is a positive thing, particularly in the final year of dissertation completion (Mwenda, 2010). However, some research has indicated that persistence among underrepresented doctoral students depends on how well integrated they are into their academic communities (Herzig, 2004). Thus, RA funding, which is more likely to engage students immediately in a research group, may be less isolating.

Figure 2. Primary Source of Doctoral Funding for 2013 Ph.D.s by Gender and Residency.

Postdoctoral Funding

This analysis includes only respondents who intend to start a postdoc in the year following graduation and either have a postdoc status of continuing with a predoctoral employer or have another firm postdoctoral commitment for the next year.

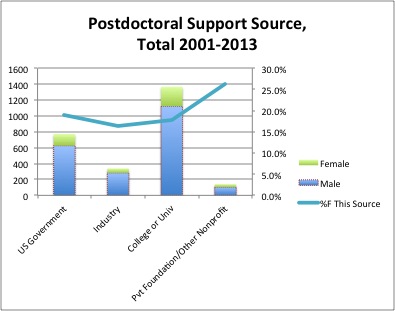

Traditionally, postdocs have not been as common in computing as in other fields, particularly the life sciences. The total number of computing postdocs began to grow about 2004, but even then there are few women reporting committed funding from most sources, making trend comparisons unreliable. Therefore, rather than look at trends, Figure 3 compares the totals of men and women receiving postdoctoral support from 2001-2013. While the funding source with the highest percent of women is private foundations and other nonprofits, by far the highest number of women are funded by a college or university, followed by the U.S. Government.

Figure 3. Postdoctoral Support Source, Total 2001-2013.

Reported Starting Salaries

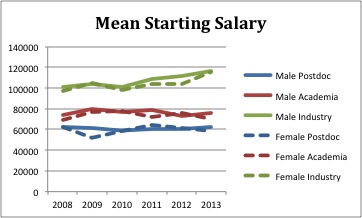

The SED has collected anticipated salary information from respondents since 2008. Figure 4 shows the mean starting salary for those individuals whose postgraduation plans were definite (i.e., returning to or continuing predoctoral employment or had a definite commitment from an employer; those who were still negotiating or seeking are not included). The category of government is omitted because of low numbers overall. There is no significant trend in the postdoc or academia salaries; industry salaries have risen for both men and women. The male salary increase is significant at .05; the female increase has a strong correlation of .60 but is not significant due to the short time frame. Clearly, the type of employment accepted had a greater influence on salary than did gender. Women’s salaries tended to be slightly lower than men’s for each type of employment. The industry difference is significant at alpha=.10 and the others are not statistically significant, probably due to the short time frame. In addition, because industry salaries are higher than the other types and because women are less likely to have taken industry jobs, the male-female gap is higher for the average salary of all new Ph.D.s than it is within any one employment type. Over the six years, the average woman’s starting salary was 93.5 percent of the average man’s starting salary.

Figure 4. Mean Starting Salary of New Ph.D.s.

Conclusions

Gender differences in the financial aspects of doctoral study interact with other differences such as residency and type of position accepted postgraduation. For primary source of doctoral funding, residency (foreign/domestic) seemed to shape the pattern of funding more than gender did. It would be interesting, however, to more closely examine the educational careers of the 20 percent of domestic women who funded their doctoral studies primarily through their own or family resources. In postdoctoral funding, the two largest funding sources (federal government and college/university) funded women at a proportion very near their representation in the pool of completing Ph.D.s. And in starting salaries, the differences between type of employment affected salary much more strongly than did gender differences. In short, there are gender differences in the finances, but overall, women don’t seem to be significantly disadvantaged.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant B2014-12 from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

Data from the Survey of Earned Doctorates was licensed through the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics at the National Science Foundation (NSF). The use of NSF data does not imply NSF endorsement of the research methods or conclusions contained in this report.

Bibliography

Bizot, B. (2014, April). Time to Degree in Computing. Computing Research News.

Bizot, B. & Zweben, S. (2015, October). Baccalaureate Origins of Women Ph.D.s in Computing, 1990-2013. Computing Research News.

Herzig, A. H. (2004, Summer). Becoming Mathematicians: Women and Students of Color Choosing and Leaving Doctoral Mathematics. Review of Educational Research, 171-214.

Mwenda, M. N. (2010). Underrepresented Minority Students in STEM Doctoral Programs: The Role of Financial Support and Relationships With Faculty and Peers. Retrieved August 29, 2015, from Iowa Research Online – theses and dissertations: http://ir.uiowa.edu/etd/560/

Schmidt, P. (2009, September 1). Doctoral Students Think Teaching Assistantships Hold Them Back. Chronicle of Higher Education.